There are thousands of pieces of property in Israel whose owners have disappeared into the mists of 20th-century history. Attorney Mordechai Tzivin is one of the few people still searching for them, hoping to return their property.

With unrest in Jerusalem turning into rockets falling on Israel from Hamas, the question of old Jewish property rights became an international concern. Israeli courts had been adjucating eviction cases of Arab tenants living on land that belonged to Jews in the East Jerusalem Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood before 1948.

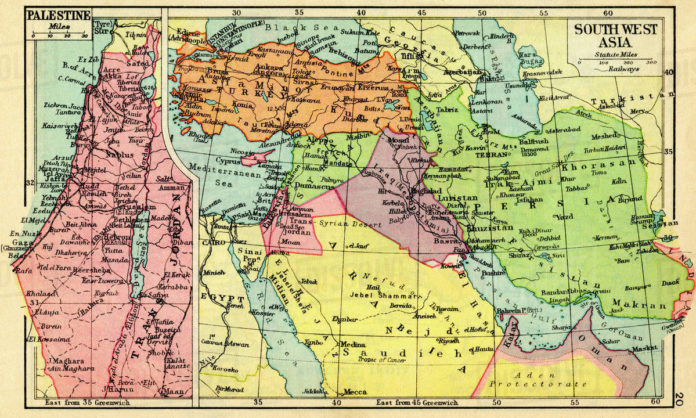

But there are other pieces of property in Israel that were bought by Jews long ago and have yet to return to them. In the 1920s and 1930s, Jews in Western and Eastern Europe, Russia, the US, South Africa and elsewhere purchased land in a number of sites in what was then Mandatory Palestine. Many of those people never saw their property. Some of them were killed in the Holocaust.

Over the years, a number of pieces of property that those people bought were returned to their heirs. The Israeli government found some of the heirs; others were found by private business people who did the research and work necessary not only to find the relatives of the lost landowners but also to convince the Israeli government, or whichever entity was holding the land, that these were the rightful people to return it to.

Israeli lawyer Mordechai Tzivin has worked on these kinds of cases for decades. He says that there are still many more parcels of land that have not been claimed. And if heirs aren’t found soon, they may never be claimed, he says, in part because the evidence that is needed to claim these pieces of property is disappearing as the years go on.

Tzivin likes to point out that getting these properties back to their rightful owners is “a true hashavas aveidah,” as he told me several times. And though for him it is a business, I also got the impression that the historical mysteries that the work presents and the sense of solving a kind of puzzle spur him on as well.

Getting involved

Mordechai Tzivin’s name may be familiar from a number of high-profile international cases, including several Jews and Israelis jailed around the world, such as the three bachurim who were arrested in Japan on drug charges in 2008. He has also represented (and still represents) a number of people from the Arab world, such as Syria, Jordan, Dubai, Libya, and Iraq, including such figures as the uncle of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. (See Ami’s article entitled “A Tale of Two People” in Issue 337, about Tzivin’s representation of a Polish-Iraqi named Ziad Cattan, who was the general director of the Iraqi defense office from 2003 to 2005.)

Tzivin says that he prefers to undertake complicated and unusual cases, including those against Israeli and international government authorities, which he says other lawyers are afraid to handle. For the purpose of dealing with these cases, he says that he uses his extraordinary connections around the world.

But he has also made time amid all of that activity to hunt for people who have property in Israel but don’t know it.

His first encounter with the issue of absentee landowners, years ago, actually started with a list of names of buyers of Israeli property that he got from an elderly American lawyer.

He also got involved in a case early on that involved a different kind of absentee landowner, a non-Jewish woman who had passed away. Agrippina Ushakoff was a Russian nun who died and left behind a valuable property in Jerusalem. Because she was a nun and had no children, finding an heir was going to be more complicated. “A friend of mine, another lawyer, asked me to get involved in the case,” Tzivin said. “I flew to South Africa. I found people by the name of Ushakoff, but they turned out not to be heirs. Then my friend went on a popular TV news program in the US, and someone from Connecticut, a non-Jewish woman, called up and said, ‘That was my aunt.’”

That case got Tzivin even more interested in the subject. And he soon began working on various situations in which people owned property in Israel but didn’t know it.

Selling to the Diaspora

Land in Israel is almost entirely owned by the state itself. “Ninety-three percent of the property in Israel belongs to the government. Only seven percent is in private hands,” Tzivin told me. He said that Ben-Gurion had argued that selling land would cause problems. “He said, ‘The land belongs to the Jewish nation. If we sell property, some rich American Jew will come and purchase all of Israel.’”

But some land is owned privately, and some of that predates the state entirely. That is one of the most interesting categories of land belonging to absent owners.

In the 1930s, a number of companies were selling land in Israel to Jews in the Diaspora. Tzivin read off a list of their names: “Hachsharat Hayishuv, Kehilat Tzion Americai, Geulah, Hanoteia, Meshek, Hachsharat Mifratz Haifa, Ma’agal, Hamanchil, Menorah, Migdal Garden Villa.”

Two of the biggest companies active in the US were Kehilat Tzion Americai, which was known by its English name, American Zionist Commonwealth (AZC), and Menorah. “They sold properties in Holon, in Afula, in Herzliya, in Gan Yavne and in Migdal [a resort area near Teveriah],” Tzivin said. He noted that AZC actually wanted the capital of the Jewish state to be in Herzliya, until the liberation of Jerusalem.

Sales of this sort went on in the US, in Europe, in Russia and in South Africa as well. Tzivin said that not always were the purchasers treated fairly. Sometimes money was paid and the land was never registered in the buyer’s name. Without any easy contact with what was then British Mandate Palestine, people who purchased a piece of Eretz Yisrael couldn’t easily check that the documents had been filed correctly. Some of them did receive deeds, though not all did.

Though there were legitimate sellers, there were also con artists at the time. That led to jokes about cheating Diaspora Jews. “There was a joke about selling land next to the opera house in Afula. There never was an opera house in Afula. There was a joke about selling property in the sea in Herzliya.”

In some cases, people paid part of the money toward a purchase but never finalized the purchase. Some were murdered in the Holocaust before they were able to. The initial money still exists in Israeli bank accounts, in some cases accounts still associated with the original company.

Tzivin told me he believes that Zionist or religious reasons were behind most of these purchases from afar. Unlike what one Haaretz article stated about the purchases, Tzivin said that most of the people who bought these properties were religious.

“I have a case where the owner left a will saying that the inheritor couldn’t marry out of the faith,” he said as one example. (That kind of clause could create legal problems, he added. “When you come to the Land Registry and you want to register the will, they tell you, ‘Hey, how do I know that he didn’t marry out of the faith?’”)

There were also people closer to the property they were purchasing who may have seen it as a good investment as well. A group of Syrian Jews who had moved to Cairo and Alexandria, Jewish immigrants from Europe, and local Jews also purchased a good deal of land in Israel. They later emigrated mainly to England, France, Canada and Brazil, and later on probably also to the US, where they have descendants who may own property that they don’t know about.

Tzivin said that some of the property of the Holocaust victims should have been protected by the Rabbanut, which became the apotropos (custodian) for property after the war, under British law. But as detailed in Professor Yossi Katz’s book, Rechush Shenishkach [forgotten property] the Rabbanut was not prepared to function as custodian for these properties.

A psak in the Rabbanut beis din in Haifa transferred the property of Holocaust victims to the Jewish National Fund and its subordinate organization, Himanuta, which had been set up to allow purchases of property that would otherwise have been problematic under British law. Himanuta had been a conduit for German Jews who wanted to get their money out of prewar Nazi Germany to purchase land in Mandate Palestine, and it also helped them purchase land after the 1939 British law forbidding commerce with enemy countries and their citizens went into effect.

With the JNF and Himanuta already holding the property of Jews trapped by the Nazis, they might have seemed like the ideal organizations to hold on to the property of Holocaust victims. After the Haifa psak, the JNF leadership approached the main beis din in Jerusalem and got a similar, wider psak.

The only holdout, at least at first, was Rav Isser Yehuda Unterman, at that time the chief rabbi of Tel Aviv. (He would later become the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel.) Rav Unterman had several demands from the JNF before he would agree to transfer the land under the custodianship of the Tel Aviv Rabbinate to the JNF. He wanted them to extend the period in which they would return the actual land to heirs, rather than simply paying them money, to ten years from five; he wanted them to pay the heirs, if they came later, a price based on the current land value, not on the value when the JNF took over the property; and he wanted some of the lands made available to religious institutions because of the large number of religious Jews whose land it was.

Chief Rabbi Rav Isaac Herzog pushed Rav Unterman into giving up his demands, which he eventually did. Thus, much of the property of Holocaust victims passed not into the hands of the Israeli government’s Administrator General but into the hands of the JNF, which has profited from it till today.

Scandals and

Swiss bank accounts

Israel’s way of dealing with these lost landowners ended up changing in the 2000s. That, according to Tzivin, was because of the scandals surrounding the Swiss bank accounts of Holocaust victims, which the World Jewish Congress protested.

In the 1990s, the idea that the money of Holocaust victims was trapped in Swiss bank accounts, with no way for heirs to access it, roiled the Jewish world. After pressure from Jewish organizations, the Swiss began to reveal which Jews had bank accounts so that their heirs could make claims.

For some Israelis, though, it seemed that Israel should follow suit. Professor Katz had published research showing that there was a large amount of property of Holocaust survivors and citizens of enemy countries as defined by the British mandate—both money and land—that was lying in Israeli bank accounts, in the hands of the Administrator General (Ha’Apotropos Haklali) of the Justice Department, or in the hands of the Jewish National Fund and its subordinate organizations.

Tzivin said: “Colette Avital argued that if in Switzerland they published the names of Holocaust victims with Swiss bank accounts, Israel should publish the names of the Holocaust victims with property in Israel. That was when they published the names.”

Ms. Avital was at the time a member of Knesset for the Labor Party. She headed a Knesset investigative committee that looked into the issue and eventually was the driving force behind a law that changed the rules about how Holocaust victims’ property was handled.

That included the creation of a special organization, Hashava, that would work to return the lost property to heirs. That organization functioned until its mandate expired in 2017, at which point its duties returned to the Administrator General.

The publication of the names of people whose property was being held by the Administrator General, however, meant that private firms like Tzivin’s could do their own searches. And the publication of names meant that even the property of people who had not died in the Holocaust was more easily returned.

Finding owners

The process of returning land to absentee landowners is a complicated one, as Tzivin describes it.

First, of course, you need to know that there is someone who purchased land or left other property. The names published by the Administrator General are helpful, but only to a certain extent. They will not disclose any information other than a name and the type of property, not even the exact kind of property and its location, that they are holding for that person, in large part because they are wary of con artists who have often attempted to falsify claims in order to take ownership of property. Tzivin said, “These strict policies of the Administrator General are positive and correct.”

Tzivin has some direct information from the original companies that sold the land, such as the list that he received from the American lawyer.

There are also ways to search through the Israeli Land Registry, if you know where you are looking. “In Hadera, there is a lot of vacant area, and we know that people from South Africa purchased this property many years ago,” Tzivin said. “Let’s say that there is, for example, Block 1000, with many parcels of property on it. You invest money and retrieve all of the abstracts—parcel number 1, parcel number 2, so on. In about 30 percent of the cases, you find that it is still registered to those original owners.” Once you have those names, you can go look for heirs.

With the names in hand, it is still exceptionally difficult to find heirs. Up until 1965, the Land Registry did not include IDs for owners, just a name. That means that you can literally be searching the globe for a Moshe Cohen, among all of the Moshe Cohens, with no indication from the Land Registry who that is beyond his name.

Tzivin said that finding the heirs requires a huge amount of detective work and that there are just five or six private business owners who are doing this type of work in Israel.

“Someone comes with an inheritance order and says, ‘Here, you see the names of the two inheritors from Moshe Gutfreund. Give me the property.’ How do you know that the Moshe Gutfreund who is registered in the Land Registry, with no ID, is the same Moshe Gutfreund for whose estate there was an inheritance order issued? You have to prove the identity of the original landowner.

“And the Administrator General is very suspicious because there are a lot of criminals who got into this field. The Administrator General is very strict in this matter, and it is good that he is, because in this way he preserves the property of the true heirs.”

“Let’s say that you know that the original Moshe Gutfreund was from New York. If you have a copy of the power of attorney that showed his purchase of the property, you can compare it to a signature of the Moshe Gutfreund whose heirs you found. If the signatures match, you know they are the same man. Sometimes we get the signatures of the person from when they came to Ellis Island.”

Because the purchases were made in British Mandate Palestine, purchasers would have gone to the local British consulate to register a power of attorney, which in turn would allow the companies that were facilitating the purchases to buy the land on their behalf. Tzivin said that these documents are still available, for example, in the British Consulate in New York, and the signatures of the original purchasers are on them. If you can match that to the documents of a known person—for example, those Ellis Island documents or a signature on a will, a driver’s license application or a passport application—you can connect the purchase of the Israeli land to that person, and therefore to that person’s heirs.

He noted that with regard to the property of Holocaust victims, this is usually much harder because so few documents remain. With those who were living in Russia when they purchased it, the search can also be very difficult, he said. “In Russia, they have fake documents like mayim l’yam mechasim.”

Not all of the property is land. “There is also money in banks that belongs to people who have died, and there is also property that the government sold for one reason or the other, but they held the money for the heir,” Tzivin noted.

“In 1978, the Israeli government announced that by December 1976, the Administrator General had been managing 1,600 monetary claims of Holocaust victims. These were people who had paid money toward buying properties, people who had bought stocks in the precursor to Bank Leumi, and people who had bought Israel bonds from the JNF and from Nir, a Histadrut-related company. The value, they said, was 12,300,000 Israeli liras, a huge amount of money.”

It requires similar detective work to reunite that property with its heirs. The Administrator General department also does some detective work to locate the true heirs in order to give them the estate.

Getting property back

One helpful aspect for the heirs is that Israel’s laws about returning property are very lenient. Even though the owners have not been paying property taxes or other fees for all of the “lost years,” the government will still return the land to the inheritors.

“I don’t know if there is any other place in the world where they will hold property for you indefinitely if you don’t come to claim it, like Israel,” Tzivin said. “The reason is that there were many people murdered in the Holocaust who have property in Israel, and it is not fair to take property from people when they didn’t have the chance to know about it.”

Still, getting it back from the government, even when you’ve found the evidence, is a process that takes some time.

“How long it takes is the million-dollar question,” Tzivin said. “We had a case involving the biggest estate in Israel that took 20 years because someone with a false will interfered. But the average is about two to three years. It takes that long because you first have to prove the person’s identity, and then you have to deal with many heirs and estates. If there was a grandfather who had three children, and each of them had four children, there are a lot of heirs to deal with. But the estates can be big.”

Tzivin noted, however, that sometimes it simply isn’t worthwhile to go to the trouble of trying to find the heirs. Because so much time has passed, there may be so many heirs for a small piece of property that it simply won’t pay. “There are pieces of property that I know will never go back to their original owners” because of that, he told me.

The Administrator General charges heirs a fee of 5 percent for administrating the property, and if the heir uses someone like Tzivin to handle the case, there are his fees as well. But the land can be fairly valuable now. Much of the property that was sold back in the 1930s is located in areas that are hot spots for real estate now.

Bringing the land back

Tzivin emphasized that there is also a good deal of land that, as in the nun case that started him off, doesn’t involve old purchases from the 1930s but instead is about property of Israelis who die and leave no clear heirs.

“[Zionist leader Zev] Jabotinsky’s sister-in-law passed away with no heirs. It was a big estate. We found a poor lady in Ukraine who was the heir.

“We had an extremely big case involving a couple who came from Russia in the 1930s. They were even accused of stealing the jewelry of the czar by a Russian delegation that came to Israel after the founding of the state. That made the front page of the Maariv newspaper.

“They died with no children, and after a long, long investigation, we found someone in Israel. The estate was $23 million. But the case took 20 years.

“The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brother-in-law, Rav Shmaryahu Gurary, known as the Rashag, had properties in Israel until now. No one knew about it but me.”

Many of the heirs who are found—whether they inherited the 1930s-era purchases or the later ones—end up selling the properties. Tzivin also noted that a number of the heirs that he finds aren’t Jewish because, sadly, their families intermarried in the interim.

But he also notes that returning the property to heirs is not the only reason to search for them. Because the properties are sitting without owners, they can’t be used. There are vacant plots in Holon, Teveriah and all of the other cities in which properties were sold, because they have no owner. “By finding an owner,” he said, “you’re also allowing the land of Israel to be used.” ●