A middle age man, a patient in a psychiatric hospital, sits in the back of a room where his doctor is explaining to a judge and to several lawyers why he needs to be given psychiatric drugs against his will.

The man tries to protest. He wants to tell the judge why the doctor is wrong. “You’ll get a chance to speak soon,” the judge reassures him.

Finally, he is given a chance to speak. With a number of teeth missing, his speech is hard make out and he occasionally goes off on a tangent. Nonetheless, he is able to put forth his arguments relatively clearly.

He tells the judge that he doesn’t like what the medications do to him when he takes them at the doses he is being prescribed. “They make me feel like I am under the influence,” he says.

His lawyer and the hospital’s lawyer argue back and forth. Was his behavior problematic enough in the hospital to suggest that he needs to be further medicated? Was his argument—that he would take a lower dose but doesn’t want the higher one—reasonable?

The judge then issues his ruling: The hospital can give the patient psychotropic drugs against his will, allowing them to do so according to a certain protocol that requires that the doctors first try drugs with fewer side effects.

This drama did not take place in a courtroom, as it would in normal times. Because of COVID-19, the proceedings are all virtual. The judge, court officers, lawyers on both sides, doctor and patient were all in different places, talking to one another on Zoom.

Many components of the court system in New York State have been shut down during the pandemic. Even urgent matters, like child support disputes, have been delayed because of the outbreak. But in Brooklyn, people who need judicial relief from the Kings County Supreme Court Mental Hygiene Court have been able to have their case heard. Not a single day has been missed because of COVID, a fact proudly noted by New York State Chief Judge Janet DiFiore.

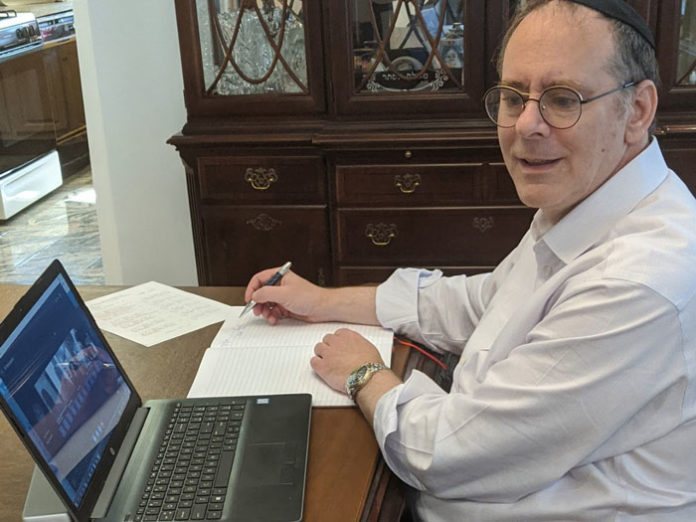

The Mental Hygiene Court is presided over by Judge Steven (Shlomo) Mostofsky, a well-known lawyer whose area of concentration was marital law for many years. He is also president of the National Council of Young Israel. Before serving on the Brooklyn Supreme Court, he was a judge on the New York City Civil Court.

According to law, when people with mental health issues are deemed a danger to themselves or others, they can be committed to the psychiatric unit of a hospital and even medicated against their will. Thanks to Judge Mostofsky’s dedication to keeping his court in session, as well as that of his law clerks and legal staff, these people have been able to argue for their rights even as others have had difficulty accessing the rest of the court system.

Having obtained permission, I was able to spend a couple of days observing cases being heard in this court. It’s hard to not be moved by the sight of people arguing for their freedom while a doctor insists that they be kept in a hospital or given a certain treatment. It is also hard not to be impressed by the team of professionals debating the best course of action for people who often have few others in the world looking out for their welfare.