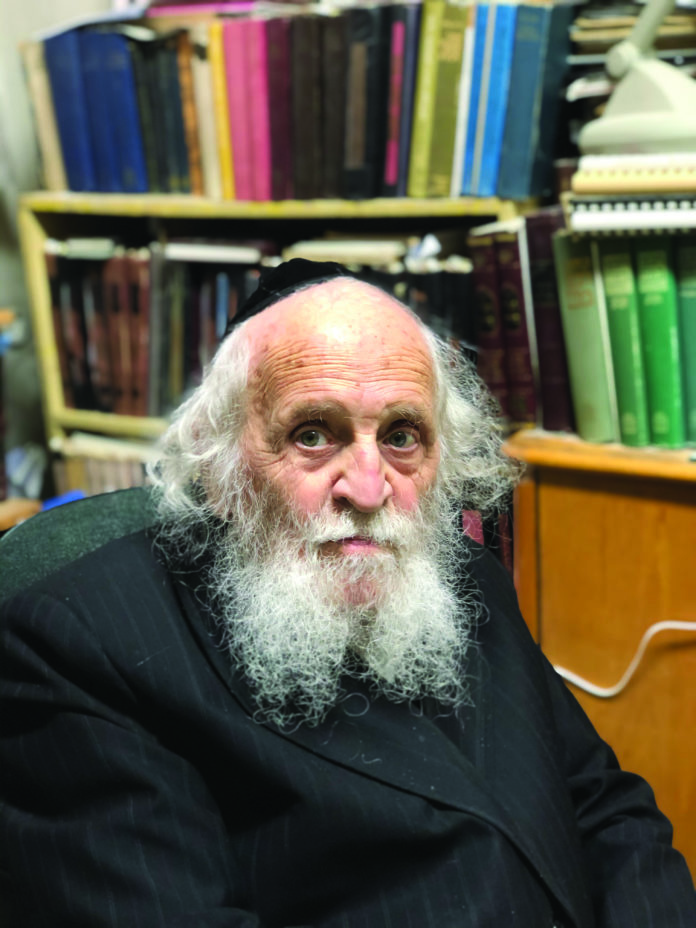

Rabbi Ashkenazi’s short, quiet and unassuming stature concealed the photographic memory of a true Torah scholar. Most people who saw him walking on the street would never believe he was such a great gaon. Rabbi Yechiel Goldhaber, a talmid chacham and author of numerous sefarim, recalled that when he was first introduced to Rabbi Ashkenazi by his father-in-law, he thought to himself, “Who is this simple-looking man?” He soon learned that “this simple-looking man” was a master of all of Torah, and he went on to become a close talmid of his.

Rabbi Ashkenazi did not usually express much emotion except to give a kind smile. But when speaking to him, he would always be friendly and polite. He was a real yekke in the sense that as soon as they bentched Rosh Chodesh Kislev, his menorah was already prepared in the window.

Rabbi Ashkenazi (né Deutsch) was born in Yerushalayim and lived in Batei Ungarin. He learned by Rav Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky of the Edah HaChareidis. When I, and others, asked him who his rebbe was, he would just smile and say no one in particular. As I grew to know him better, I realized that Rabbi Ashkenazi’s friends and teachers were his sefarim and his pen.

First Encounter

Back in 2000, when I was still a yeshivah bachur learning in the Mir, my friend told me about this astounding talmid chacham named Rabbi Shmuel Ashkenazi, who knew kol haTorah kulah. Sometime later I was in a sefarim store and noticed a thick sefer, over 800 pages long, called Alfa Beta Kadmita diShmuel Ze’ira. I opened it and realized that it was written by the same Rabbi Shmuel Ashkenazi I had just heard about. I purchased the sefer, and as I began looking through it, I could tell that my friend had not been exaggerating. It appeared that Rabbi Ashkenazi did, in fact, know anything and everything connected to Torah.

I first met Rabbi Ashkenazi the same way most people did. I had a scholarly question for which I could not find an answer and which no one was able to resolve for me. At the time, I had been working on researching and publishing my first article, which involved tracing the source for the custom of not sleeping on Rosh Hashanah. One of the earliest sources quoted was in the name of a part of the Yerushalmi that appeared to have been lost at some point. While I was researching, I learned that Rabbi Ashkenazi was planning on writing about this topic in his next volume. So, when I returned to Eretz Yisrael in 2004, one of my first planned stops was to pay him a visit.

When we met, I discovered that we shared a love of sefarim as well as a thirst for knowledge on a wide range of topics. From then on, I visited him very often—up until a few weeks before the coronavirus got in the way of our ability to socialize. Even then, I would try to speak to him on the phone.

Rabbi Ashkenazi was an avid reader and would read everything he could get his hands on: newspapers, books, sefarim; he was just curious about everything. I visited him at many different times of the day, even late at night. Even when he was over 90, I would always find him bent over a book. This thirst for knowledge contributed to his expertise in so many different topics, whether it was Tanach, Chazal, halachah, minhag and chasidus, or more specific subjects such as tefillah, piyut, dikduk, Kabbalah, machashavah, philosophy, history and bibliography. In all of these areas, his knowledge was remarkable.

What was incredible wasn’t just that he was learned (after all, many people have that acclaim), but that he would collect and catalog much of what he read and would have that information ready at his fingertips.

When I was working on an article about the Dikdukei Sofrim I looked for the haskamos that were recorded in the first edition of the work. I had searched numerous copies, as had others, with no luck. Late one night, I came to Rabbi Ashkenazi’s house and mentioned my problem. He instructed me to take down his copy of the sefer, and lo and behold, it was a first edition with the missing haskamos! I published the missing haskamos in my article on the Dikdukei Sofrim, attributing this rare find to his library.

Indeed, Rabbi Ashkenazi’s filing method was one that only his brilliant mind could comprehend. Often, he would collect information on a particular topic and place it in a related sefer and periodically update his notes from there. It was common for me to come across notes written in the margins or in a paper tucked into the sefer that would be related to what I was searching. Other times I would find something else that was of great importance. Rarely did I leave his house empty-handed.