Hauptsturmführer Amon Göth was the commander of the infamous Plaszów concentration camp, which was built in 1942 on land belonging to the Jewish cemetery of nearby Kraków. It was intended to serve as a forced-labor camp for the Jews of the Kraków Ghetto, but by 1943 it also served as a concentration camp, where inmates were starved, tortured and shot.

My father and I were both interned there and did hard labor. Göth was known for his extreme cruelty and delight in shooting Jews at random and without provocation. He would roam the camp accompanied by attack dogs that he would sic on prisoners if he didn’t like the way they looked; I still have scars from those dogs. My father would tell me, “Yossel, do whatever you are told. Just bow your head and do it.”

The worst thing you could do was to attract Göth’s attention. He once pulled a handsome Jewish man out of a lineup, and after remarking that he wouldn’t permit a good-looking Jew into his camp, shot him dead on the spot. He was the angel of death, and I was determined to do whatever I could to bring him to justice.

I was a 13-year-old kid with long curly peyos when the German tanks rumbled into Kraków that fateful September. I watched as the long columns of Wehrmacht soldiers marched in goose-step along the ancient cobblestone streets of the historic city. Like everyone else, I was curious to see the parade of occupation forces on Kraków’s main avenue. I remember that one of the tanks suddenly stopped, and out popped the head of a soldier who glanced at us and asked politely in German, “Where can I find some aspirin?” I pointed him in the direction of a nearby pharmacy, and he thanked me with a polite “Danke schoen.” The Germans seemed very civilized and pleasant. No one could have anticipated the magnitude of the horror about to begin. I had no idea that I would soon have to cut off my peyos or that life as I knew it was coming to an end.

I was born in 1926, the oldest of three boys and two girls, in a town called Dzialoszyce, located not far from Kraków in southern Poland. My family owned a flour mill and several other businesses. I remember our shul; to me, it was as big as I imagined the Beis Hamikdash to have been. When I went back after the war, it was in ruins. My father moved the family to Kraków when I was seven. We lived in a large, imposing house that has since been turned into a police station.

The Jewish part of the city was known as Kazimierz. It was filled with Jewish merchants who spoke Yiddish as they plied their wares, as well as rabbis, shuls and shtieblach. My father was a wealthy man from a well-established family. The lane we lived on was even called “Lewkowa Street,” named after us (Lefkowitz). We lived in the heart of the Jewish quarter and had a shop on the main square. My father was a Bobover chasid, and we davened in the Bobover kloiz, which serves as a bookstore today. I can still remember the feeling of excitement when the Rebbe, the Kedushas Tzion of Bobov, came for a visit, and how the streets of Kazimierz would fill with people.

The main shul was known as the Izaak Shul, one of the largest and most magnificent shuls in Poland. It has become functional again in recent years, and I dedicated a sefer Torah to it. The famous Rema Shul was just a block away from our house. Lag BaOmer is the Rama’s yahrtzeit, and tens of thousands of Jews from all over Poland, and even Russia, Germany and Holland, would flock to the city to mark the day. The whole plaza in front of the Jewish cemetery was crowded with people who came by carriage from the train station. Tables were set up in the adjacent streets for kvitlach writers, booksellers, bakers and other vendors. I could barely get out of the house that day, and if I did go out, I would have to elbow my way through the crowds to get home.

After Hitler came to power in Germany, the Polish Jews who had gone to live there to escape their dire poverty began to be deported back to Poland, despite the fact that many of them had already become part of German society. The shuls in Kraków raised money for them, holding fundraisers and finding them housing. But no one thought that we too might be affected by what was going on. Our relationship with our neighbors was good; we were Polish citizens just like they were, protected by law.

Jews had lived in Poland for hundreds of years. The Jewish quarter was named after King Casimir the Great, who loved and protected the Jews. As in the Purim story, Casimir had a Jewish wife named Queen Esterka, who used her position to save her brethren from persecution by the Catholic priests. Every major Polish city had a street named after her, and Kraków was one of the most important Jewish communities in Poland. Who could have imagined what would happen next?

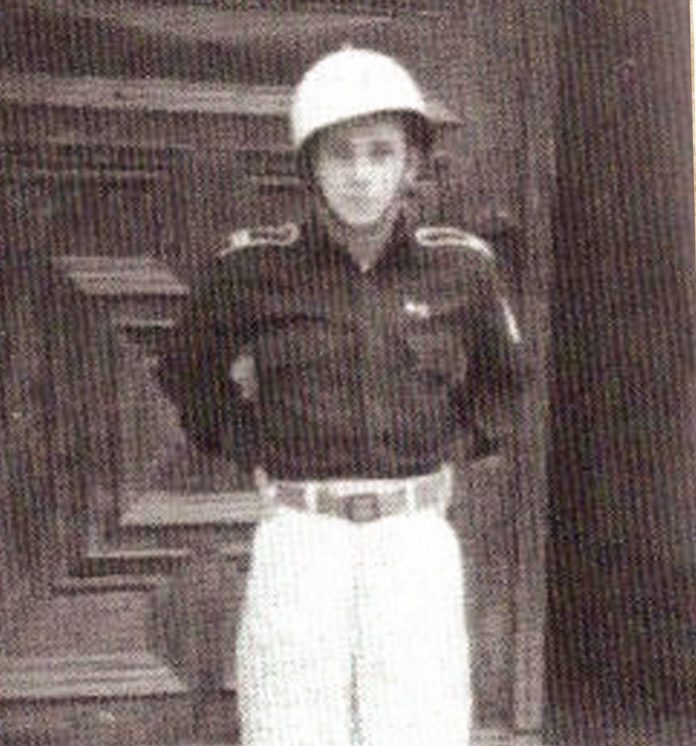

In 1939, when Adolf Hitler first threatened to invade Poland, the Polish army began preparing its troops for war. My father was drafted and sent off to the front in his uniform. We were sure that our army would be able to stop the Germans if they dared to invade our country. The young people were also recruited to dig protective trenches along the city’s perimeters.