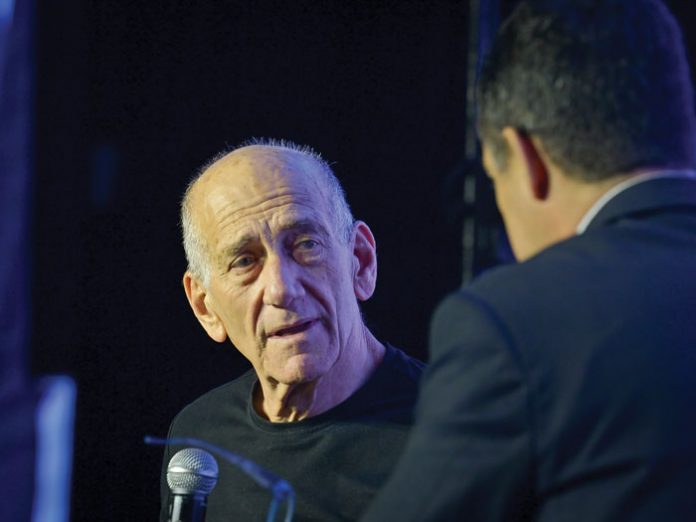

If you would meet Ehud Olmert, the former prime minister of Israel, today, you might have a hard time recognizing him. The last time we spoke he looked hale and had a bit of a paunch. Now he looks thin, almost gaunt, and seems to have aged a number of years. He was released from prison a year and a half ago after being convicted, along with a group of Jerusalem municipality officials, of accepting bribes to promote the controversial Holyland real estate project in the capital.

Perhaps his years in prison have changed him physically, but when he opens his mouth there is no mistaking the sharp tone, wit and spark of mischievousness in his eyes. None of that has changed. Nor has his self-confidence or determination.

“Prison did not change me,” he insists. “Maybe lately I’m not eating enough, but I’m on a diet. I lost weight and slimmed down, but I’m healthy.”

Olmert is still Olmert, even after a long stint in Wing 10 of Ma’asiyahu Prison, but it is hard to believe that prison did not change him in any way, for better or for worse.

“I really haven’t changed,” he insists. “Maybe I’ve had time to think and become a little more attuned to what’s happening to other people, but in essence I’ve remained the same.

“I know,” he continues, “that there were rumors that I became a baal teshuvah in prison. The chareidi newspapers printed reports to that effect. They said I was putting on tefillin. The truth is that I have always respected religion and tradition. For years I have been studying Judaism on a regular basis with an acquaintance. I did not become chareidi in prison. But there were ten of us in the same wing in prison. Some of us were dati and some were chareidi. Others weren’t religious at all. The religious ones wanted to have a minyan every morning so I said to the other guys, ‘It’s not like you have a calendar full of important meetings or business decisions to make. We all have lots of free time, so why not help make a minyan for the others?’

“So that’s what we did every morning. Sometimes I said Kaddish. On the days when there the Torah was read they honored me with ‘shlishi.’ Sometimes I even made Kiddush on Shabbat.

“In general,” he adds, “I gained a lot of respect for the chareidim I was with in there.”

For many years Ehud Olmert was a prominent and influential figure in Israeli politics. He began his career as one of the “princes” of Likud, coming from an old Revisionist Zionist (right-wing, not religious) family. He was first elected to the Knesset in 1973 at the age of 28. Together with Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, he left the Likud Party in 2005 to establish Kadima. When Sharon suffered a stroke after the elections Olmert took his place, and went on to serve as prime minister from 2006 to 2009.

In 2014 Ehud Omert was convicted in the Holyland land development case and on other charges of bribery and breach of trust dating back to his tenure as mayor of Jerusalem. Upon appeal he was acquitted in the Holyland case and his sentence was reduced, but his conviction in the related Hazera bribery case still stood, and he was imprisoned until the summer of 2017.

After several years of refraining to comment on the political scene, with the start of the recent election campaign he became one of the most prominent and outspoken critics of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who ultimately won the election.

Olmert never hid the fact that he supported Blue and White, and voted for Benny Gantz and Yair Lapid. In fact, he continues to attack Netanyahu with his characteristic acrimony, although he denies that he would like to return to the political arena.