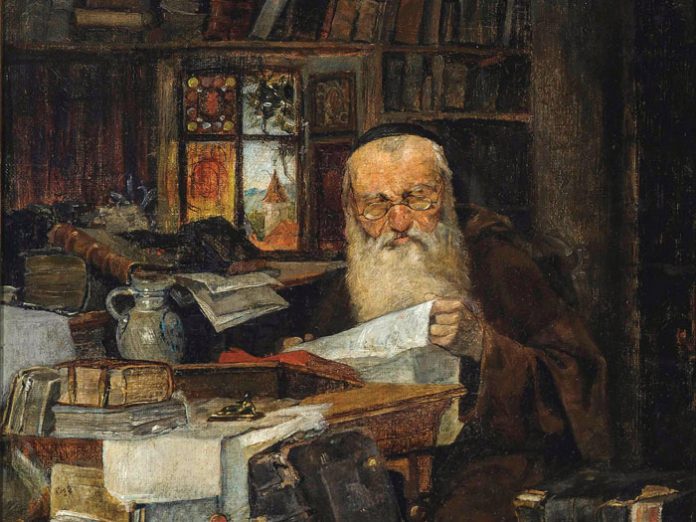

n every Jewish home, you can turn to the bookcase and find a collection of sefarim. You can walk into a shul or beis midrash and find its otzar hasefarim. Jews collect sefarim and have done so for thousands of years.

There are some, however, who make an art out of collecting. That can be the private collector, with thousands of sefarim arranged in his home library. Or it can be an institutional librarian or curator, carefully arranging a collection so that the public can use it.

These libraries include the largest collection of sefarim in 18th-century Europe, one man’s attempt to own every Jewish book, as well as the largest Jewish library of the modern age, with a mission to collect every Jewish work in existence.

What goes into creating and maintaining these collections? What can we learn from them? To get answers to these questions and more, we spoke with a number of the individuals who have been involved in collections, to hear their stories, and the stories of the collections they’ve been involved with. Each interview asks a question about the world of sefarim collections. Here are the answers.

How Do You Create a Private Collection?

Pinney Stieglitz explains how he hunted for sefarim and built his library

Love of sefarim is widespread among Jews. But how do you go from that affection to actually creating a library? To get an idea, I spoke with Pinney Stieglitz, who has been hunting books for decades.

“I started about 45 years ago,” he said. “It started in 1974 when my grandfather gave me the first edition of the Rambam with the Kesef Mishneh. Once I got that, it piqued my interest and I began collecting.”

And his collection grew. “I’ve sold a lot of sefarim, so I’m down to about 2,500,” he said. “At one time, I had about eight or nine thousand sefarim.

“The main focus of my collecting has always been books from Venice, 16th century, Hebrew printing, what we call the shins.” That is, sefarim printed in Hebrew years starting with the letter shin.

Why those sefarim in particular?

“I found that to be the most beautiful Hebrew printing, and the quality of the sefarim usually was very good.”

He has several things he looks for when deciding whether to buy a sefer.

“Number one, the city of publication. Venice is something that I really appreciate. The printing should be between 1540 and 1640. It should be a topic that I’m interested in—Talmud, Rambam, teshuvos, drush, sefarim on Torah or Tanach. And the quality of the paper, the quality of the printing, the binding—all these things go into the purchasing of the book.”

How has he found sefarim? In the same manner that Rav Dovid Oppenheim did back in the 17th century: by buying other people’s private libraries.

“It’s the only way to do it,” Mr. Stieglitz said. “You can go to auctions, but then you’re paying retail prices, which doesn’t appeal to me. So I bought a library, culled the things that I wanted and sold the balance to pay for the sefarim. And that’s the way I built the library. Of course I buy from dealers, also, but when I built the library originally, I did it by buying private libraries.”