My family’s home in Modi’in contains a library of very old sefarim, its shelves filled with worn and delicate manuscripts. There are ancient sefarim that date back to the earliest days of the printing press and have been passed down from generation to generation in our family, including Gemaras, Chumashim, siddurim, Tehillims, and sefarim of the Rambam. These sefarim are rare indeed, but they are not just intended for display. They are not meant for book collectors and kept immaculately clean behind glass. The manuscripts are worn from years of use, their pages crumbling and yellowed with age, stained from centuries of fingers leafing through them. Some pages are stained with tears, and I can only wonder how they got there…

The sefarim are imprinted with the signatures and inked seals of eight generations of the Frankel family, as well as the inked stamp of my holy grandfather, Meir Schor, who together with my grandmother Mila, perished so horribly 70 years ago. May Hashem avenge their blood.

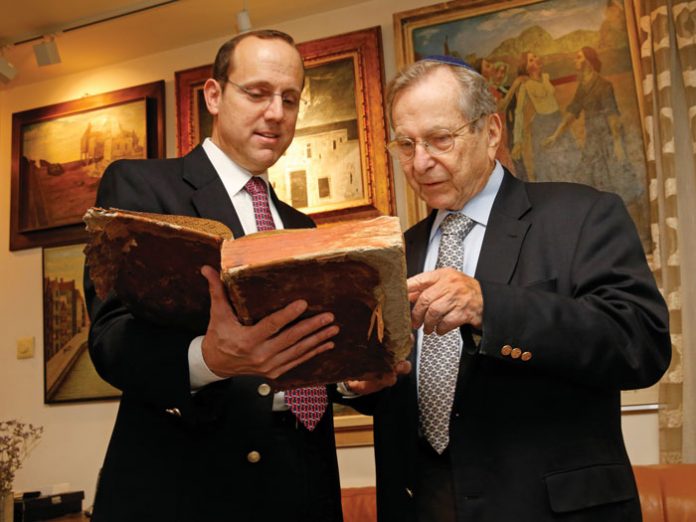

But one sefer, the Sefer Mitzvos Gadol (Semag) of the 13th-century French Rishon Rav Moshe of Kutzi, is especially ancient, and is one of the first Jewish books ever printed. But what is unique about it is that this sefer contains on its title page, in addition to the seals of my predecessors over the generations, a stamp in German letters that reveals a chapter of this sefer’s story. It is a story of darkness and melancholy, of night and dawn, of the destruction and the nechamah of my family.

Our story begins in Kraków, Poland, where my grandfather, Meir Schor, lived. Zaide had yichus, coming from a long line of gedolei Yisrael, beginning with the gaon Rav Alexander Sender Schor, who was born in 1673 and was a great halachic authority. He was known by the name of his sefer, Tevuos Shor, one of the fundamental sefarim dealing with the laws of shechitah and kashrus. My grandfather’s legacy was this amazing library that was assembled over the centuries.

My grandmother, Mila Schor née Frankel, was from Tarnow, Poland. Her father was Berl Frankel, a descendant of rabbis and scholars for many generations. The Frankel family had an extensive library containing rare books and ancient manuscripts.

After my grandfather’s in-laws passed away, Berl Frankel’s sefarim were integrated into Meir Schor’s own library. My grandfather was very proud of this combined literary treasure, which was well-known in Kraków, and he guarded it carefully.

One of the most unusual sefarim in the library was the first edition of the siddur of the Shelah Hakadosh. As the siddur was passed from generation to generation, every owner added their signatures inside.

My grandfather was a successful merchant as well as a scholar. He raised his family in Kraków. He had one daughter who married and moved to Katowice, and a younger son who was named Berl, after his mother’s father, Berl Frankel.

In 1939, the clouds of war began to form over Europe as Germany began making threatening moves against Poland. No one thought that the Jews were in any particular danger, nor did anyone think that the Germans would succeed in conquering Poland so quickly.

As it happened, my grandfather and grandmother, Meir and Mila, had Turkish citizenship. It is not entirely clear to me how they got it, but it seems an earlier relative acquired it when he lived in Turkish-controlled territory—perhaps Romania—and it transferred to the next generations. Turkey was neutral and therefore, my grandfather believed, its subjects would be protected in case of war. His Turkish citizenship would safeguard him; he had nothing to fear from the Germans.

On Friday, September 1, 1939, my grandfather’s home in Kraków was preparing for Shabbos. His daughter and son-in-law had come from Katowice to spend Shabbos with the family. Suddenly, the air was filled with the wails of sirens: Kraków was being bombed by German planes. World War II had begun.

Zaide was not afraid of the Germans. Like most, he expected that the fighting would continue for a long time before the Germans would conquer Poland. No one expected the Polish army to be defeated in just over a month.

To Lublin and Beyond

But Kraków, located in southwestern Poland, was very close to the front, not far from German-occupied Czechoslovakia. For peace of mind, the family decided to evacuate primarily the women and children to Lublin, in eastern Poland. My grandfather was a wealthy merchant and owned a car, but it was confiscated by the Polish army, so my uncle managed to find a bus to transport the family members to Lublin. He even managed to get enough fuel for the bus ride, even though it was strictly rationed.