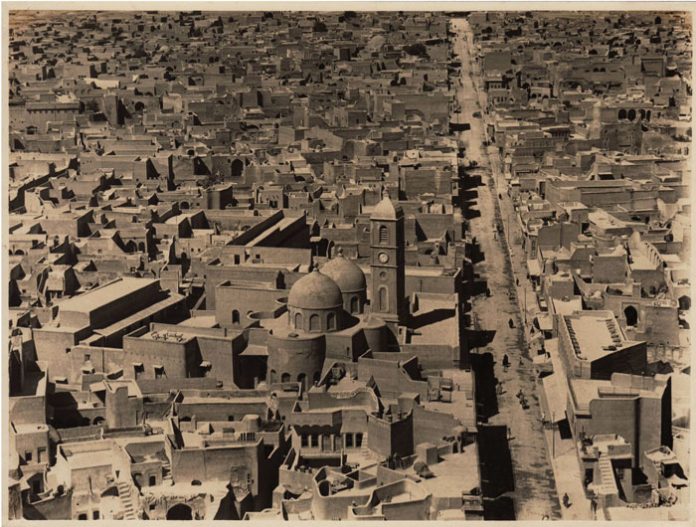

Liberation Square, Baghdad, January 27, 1969

“You cannot kill us! You murderers! I have three children, and my wife is pregnant!”

Soon, though, the tranquilizers the men had been given dulled their brains and they were dragged to the gallows.

The radio had started blaring at six that morning, with music and trumpets and an invitation for all citizens to enjoy a day of festivities in Liberation Square in the center of Baghdad.

“Great people of Iraq! People of Baghdad and Basra! Today is a holy day for all of you! Today is your feast! The day of your joy and happiness! The court has finished its deliberations and sentenced the traitors to death! Go now to the Square to see them hanged!”

That day the trains and buses were free, so that masses of people—500,000 Iraqis in all—would converge on Liberation Square, smiling and laughing as they made their way to the party. Dancers entertained the crowds and the hordes cheered and howled as the barefoot “traitors” were hanged from the gallows, dressed in brown linen pants and shirts, their hands covered in white gloves to hide their tortured fingers. Each one had a sign around his neck stating his religion in large letters, followed by the accusation against him beneath it in smaller ones.

Their bodies were left on the gallows the entire day. The crowds cursed them, threw stones and spit at them. Some tried to jump high enough to pull their feet in the most shocking disregard for human dignity.

And throughout the day the radio announcer continued to intone, “Great people of Iraq! People of Baghdad and Basra! Today is a holy day for all of you! Today is your feast! The day of your joy and happiness! The day on which you have gotten rid of the first gang of despicable spies! Your beloved Iraq has executed these traitors and settled the account. Great people of Baghdad and Basra, go to Liberation Square to see with your own eyes how the traitors are hanged.”

Then he would read the names of the nine Jews again and again, all day long.

Ezra Naji Zilka.

Raphael Horesh.

Yehezkel Gourji Namerdi.

Sabah Haim Dayan.

David Ghali.

Fouad Gabbay.

Naim Khedouri Halali.

Heskel Saleh Heskel.

David Heskel Baruch Dellal.

Rimon: Son of Fouad Gabbay

Basra, October 1968

I was seven and a half years old the day I came home from school with my five-year-old sister Rita and saw the cars in front of my house. I was sent to a private school in Basra. There were no more yeshivahs, because most of the Jews had left, but we attended medrasha after school. My little brother David stayed home with my mother. Even though we weren’t a big community anymore, the Jews who were still in Iraq were the wealthiest people in the city. My grandparents owned lots of real estate. We were the kings. We had a large, luxurious home, with a lot of servants, and my father was one of the only people in town who had a car. It was an olive-colored Chevrolet, one of a kind, and it was very expensive.

From the moment I stepped inside my house the innocent, carefree life I’d enjoyed as a child abruptly ended. In the front hall, five or six policemen were beating the Kurdish man who helped us with the cleaning. The Kurds were considered to be illegal immigrants, even though Iraq was their home too. They would punch him over and over again, and then push him to the next group of men to be punched again. When they were done beating him they moved onto my mother. The Kurd took this cue and escaped. We never saw him again.

Four of the men, big and burly with thick Nazi-like mustaches, then pushed my mother onto the floor and held her down.

“Nurid ‘an naraa jamiye alghuraf! We want to see all the rooms! Your husband is a spy! He aided Israel in the Six-Day War!”

The policemen went up to the master bedroom and came marching back down, holding the transformer of the air conditioner that had been above my parent’s dresser. This was supposedly my father’s specialized device for communicating with the Israelis.

“Ayn aljasus? Ayn aljasus? Where is the spy?”

My father knew they were there, but he wasn’t home yet. Every day after work he would stop by my grandparents’ house to visit before coming home. My grandparents lived only 400 yards away and all the Jews lived in the same neighborhood, so everyone had already seen the cars of Saddam’s secret police parked in front of my house and word had reached my father. They had warned him not to go home because he was a wanted man.

My grandmother told my father to flee. Any visit by the secret police was a bad sign.

But my father was worried about us. And besides, what could they accuse him of? So he went home. But he never even made it inside. As soon as he pulled up they grabbed him out of the car. As the police were holding him, my four-year-old brother David ran out to hug our father.