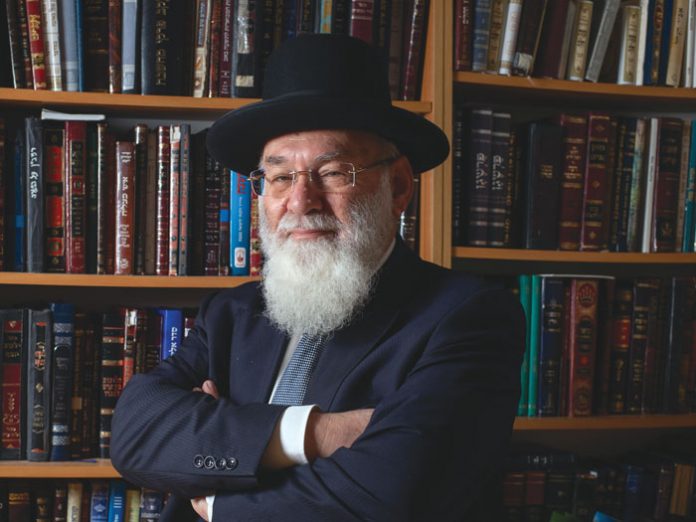

For anyone who enjoys the company of a smart person, being in the presence of Professor Avraham Steinberg is a singular experience, since they don’t come much smarter or with more credentials than him. Just pinning him down to a simple job description or identifying him with a single title or honorific is close to impossible. For starters, Professor Steinberg is a practicing physician—a pediatric neurologist, to be precise; a medical ethicist of note; an author of numerous award-winning sefarim on halachah; and the editor of the Encyclopedia Talmudis. The good professor has also served as an adviser on medical ethics to the Knesset and Chief Rabbinate of Israel, and he has been involved in the halachic aspects of modern medicine in consultation with the most prominent rabbinic authorities of the previous generation, including Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Rav Shmuel Wosner, Rav Yosef Sholom Elyashiv, Rav Ovadia Yosef and Rav Eliezer Yehuda Waldenberg.

Up until recently, he worked as a senior pediatric neurologist at Shaare Zedek Hospital in Jerusalem and taught Medical Ethics at the Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School. He also chaired several Israeli committees on bioethical issues, including the National Israeli Committee for Evaluation of Living Organ Donors, the National Advisory Committee to the Minister of Health for Enacting a Law Concerning the Terminally Ill, the National Ethics Committee in Accordance with the Dying Patient Act (2005), the National Advisory Committee for Amendments of the Anatomy and Pathology Law, and the National Forum Concerning Organ Donations in Israel.

He presently serves as the director of the Medical Ethics Unit at Shaare Zedek and as co-chairman of the Israeli National Council on Bioethics. Professor Steinberg is also a member of the halachic committee of Magen David Adom, chairman of the Board of Mohalim of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate and the Ministry of Health, and a member of the Committee for Medical Matters and the Interreligious Dialogue Committee of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel.

However, as I discover when I meet with him in the offices of Yad Harav Herzog on Rechov Shmuel Hanagid in Yerushalayim, where he serves as the head of the Encyclopedia Talmudis that Yad Harav Herzog produces, despite this mindboggling resume, Professor Steinberg is a self-effacing and accessible man as well as a gracious host.

In fact, one might describe him as a true Renaissance man, an ideal that originated in Italy during the Renaissance and was more recently defined by the Italian thinker and writer Umberto Eco as someone who is “interested in everything and nothing else.” To me, though, it brings to mind the notion of Torah im Derech Eretz, the idea that one should be erudite in both Torah and other fields of knowledge that Rav Shamshon Rafael Hirsch popularized in Germany. So I’m surprised when he tells me that although he was born in 1947 in the Displaced Persons Camp in Hof an der Saale, Germany, his family doesn’t hail from Germany but from Galicia.

“My father, Rav Moshe Halevi Steinberg, my grandfather and my great-grandfather were all born in Galicia. My grandfather and great-grandfather served as rabbanim of the chasidishe shtetl of Premishlan. The Baal Machazeh Avraham, the rav of Brod, was my great-great-grandfather.

“My father’s ancestors weren’t Premishlaner chasidim. I don’t know if there were any Premishlaner chasidim at that time; they were Tchortkover chasidim. There’s actually a teshuvah from the Machazeh Avraham in which he writes that he can’t answer a sh’eilah right now because he is an aveilus after the passing of the Tchortkover Rebbe; he was one of the maspidim of the first Tchortkover Rebbe.

“As it turned out, my grandfather married someone whose family was close to Belz, so as an eidim he became a Belzer. Then during World War II, when the Belzer Rebbe came with his family to Premishlan, he told my father, who was serving as a meshamesh of his grandfather, the rav of the city, that they should immediately escape, because the Germans would kill the rabbis as their first act. ‘But what about the Rebbe?’ my father asked him. ‘What can I do?’ he replied. ‘I have 70 people here; how can I run? But there are only two of you, and you must escape.’ That’s how they were saved. My father lost his entire family except for a brother. I was a year old when my parents came to Eretz Yisrael. Once here, my father was appointed rav of Kiryat Yam. I’m an only child, and my father passed on to me the Galicianer way of learning rather than the Litvishe way. In Galicia there were no yeshivos until Rav Meir Schapiro. Everyone learned in the shtiebel with the rav. Until my late teens my primary rebbe was the rav of the city, my late father.”