If you were living in Europe in 1870 and you had a halachic question, which rav would you have sent the question to? You might have chosen Rav Yaakov Ettlinger, the rav of the German city of Altona, the author of the Aruch LaNer and Teshuvos Binyan Tzion. It’s also possible you would have sent it to the Maharsham, Rav Shalom Mordechai Schwadron, of Berezhan, in present-day Ukraine. Both were major poskim whose teshuvos were sought by communities and individuals across Europe and around the world. But which one of them would you have chosen?

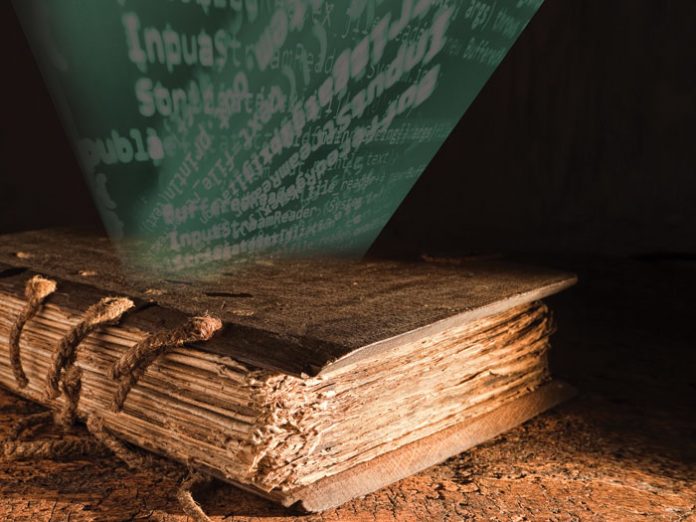

That sounds like a strange and theoretical question, but a new computer project might soon be able to tell us—and open up our understanding of—how halachah and Jewish life have developed over time.

Go into any full beis midrash, and you’ll find one person who is fascinated by a specific kind of sefer: sh’eilos u’teshuvos (halachic responsa). There are plenty of reasons to be entranced by shu”t. For one, they often involve the knottiest of practical halachic problems, dealt with in-depth and creatively by some of the greatest talmidei chachamim. They often illuminate sugyos in Shas in a way that you might not have gotten simply from learning the sugya with the Rishonim and Acharonim there.

But there are also other aspects of sh’eilos u’teshuvos that are fascinating. Sometimes the sh’eilos, the questions, involve interesting stories that illuminate the circumstances of Jewish life at the time they were written. Sometimes the teshuvah, the response, gives an idea of who the gadol or rav who wrote it was.

A new digital project is mining sh’eilos u’teshuvos for another aspect that makes them fascinating: the place and date they were written and to whom they were written. The project, called HaMapah, is mapping the physical and temporal composition of shu”t, and as the project’s organizers explained to me, that can help explain numerous aspects of the development of halachah over the centuries.

From Baseball to Shu”t?

HaMapah is the brainchild of Rabbi Elli Fischer and Moshe Schorr. Rabbi Fischer, a talmid of Yeshiva University and a musmach of the Israeli Rabbanut, was previously the JLIC rabbi and campus educator at the University of Maryland. An independent writer, translator, and rabbi, he is now working toward a doctorate in Jewish history at Tel Aviv University. Mr. Schorr is a talmid of Yeshivat Har Etzion and is now a computer science student at the Technion.

Their collaboration, Moshe said, started with discussions about applying statistical analyses to sh’eilos u’teshuvos.

“We realized no one had done this systematically,” he told me. “People had done it small-scale in the ’80s, early ’90s, before you had good computerized analyses available. We had the expertise to do it.”

Rabbi Fischer said that he has had a longtime interest in the so-called metadata of shu”t.

“A number of years ago, I did a project for Sefaria in which I translated about 40 or 50 sh’eilos u’teshuvos. One of the things I did was create a database with all the teshuvos I was going to be translating, and I put in this data: when it was written, where it was written, who it was written to. I tend to think that sort of data is important to understanding sh’eilos and teshuvos.

“In the yeshivos, one of the first things you learn about sh’eilos and teshuvos [is that] they’ll say they were just saying that for a particular time or a particular situation. For example, you’ll see people saying that Rav Moshe Feinstein’s teshuvos on ‘chalav hacompanies,’ or what’s now called chalav stam, he only meant as a b’di’eved for the situation in America. They’re saying that historical context is very important for understanding what’s going on in a teshuvah.

“There’s a similiar tendency in the academy over the last number of years—there’s even a book by this name, Hashut K’Mikor Histori—of using sh’eilos u’teshuvos as a historical resource. You mine the teshuvos in order to understand the history around them. We’re taking an opposite approach. For us, it’s more like historia k’mikor lashut. When you understand the history, the better you understand the teshuvah.

“This has been my thinking for a few years. I wanted to do something with this but never did. Moshe was reminding me about it. There was an online conversation about analytics in baseball and what’s called sabermetrics, advanced statistical analyses that have changed, in some sense, the way the game is played and even more the way the game is measured, the way we think about phenomena that have been part of the game forever, and it sort of grew out of that.

“Moshe had always taken a very strong interest in this, and about a year ago he brought it up, asking me, ‘What’s going on with this?’ It was right before the World Congress on Jewish Studies. I said, ‘Let’s see if there’s interest in this.’”

At first they wanted to see if anyone was interested in funding this project, but then they realized that they needed to create a proof of concept. They needed to start the project; then funding would come.

“We think it’s a fantastic idea and people will want to get on board,” Rabbi Fischer said.

Making a Robot Learn Torah

The basic data needed for this project is the metadata—the author of a teshuvah, where he wrote it, when he wrote it, and which town the person who sent the sh’eilah was from—but it’s not so easy to gather that data, even with modern digital compendiums of shu”t.

“The process of entering all the data by hand would be extraordinarily time-consuming and painstaking,” Rabbi Fischer said. They have reached out to scholars who do have some of that data, for specific sefarim. And they are also using computer programs to sweep through shu”t databases, like Bar-Ilan’s, for this kind of information. But that’s easier said than done.

“The one thing we are doing pretty much by hand is identifying places,” Rabbi Fischer told me. “That’s a very tricky part of the process. There are abbreviations, and there are typos.

“Let’s say we have all the teshuvos of the Chasam Sofer. How do I teach the computer how to find places? One way is through certain terms that always come up before a place name. For example, aleph beis daled, for av beis din, means that the next word is going to be the name of a city. Or kuf with an apostrophe or kuf kuf, kehillah kedoshah, or moreh tzedek.

“So we’ve iterated this list and we run it through, and we’ll see if there’s any way we can update the script to grab more names.”

What they end up with then is a list of place names. But figuring out what the names refer to may not be so simple, if it’s possible.