There are plenty of beautiful megillahs that you’ll see on Purim, some illustrated, some with clear large letters, some laid out strikingly on the page. But in one beis midrash in Eretz Yisrael, you were able to see a megillah you would see nowhere else.

My father, Rav Yaakov Schwartz, z”l, was one of the chashuve Gerrer chasidim in Tel Aviv. He had a beautiful custom that he would fulfill on the night of Purim after the reading of Megillas Esther. After saying the piyut of “Asher Heini,” which describes how Hashem heard Mordechai and Esther’s prayers and brought an end to Haman’s evil decree, my father would organize a circle of men to gather around him.

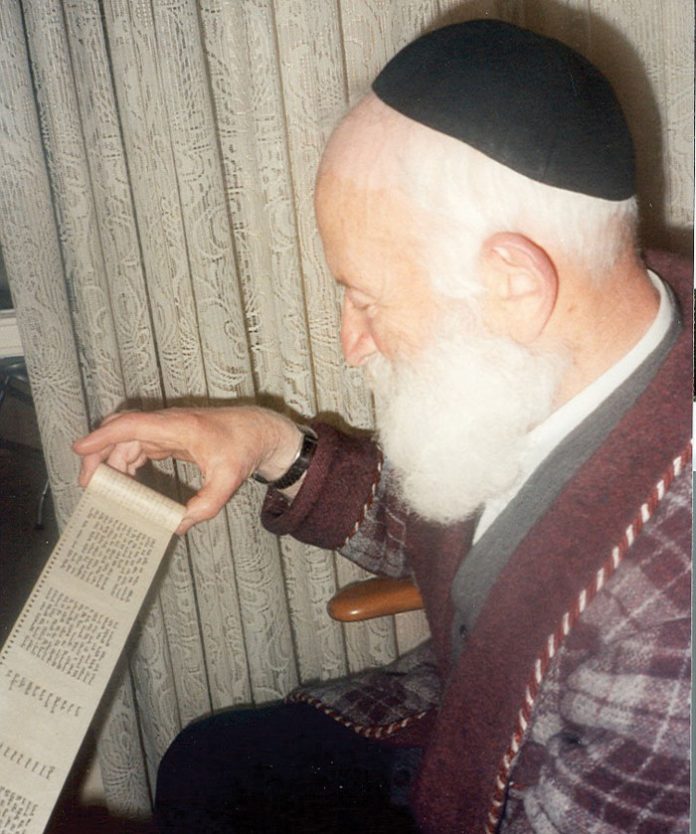

The chasidim in the shtiebel would dance around him as he held in his hand a tiny megillah that he would spread wide like a sefer Torah. The megillah was yellowed with age and the scroll itself was made of paper. Together, all the chasidim sang Shoshanas Yaakov, but my father’s voice was the loudest of all. He would scream “Arur Haman” until he was hoarse, and all the chasidim would stamp their feet in reply. For him and those who knew his story, this Purim dance was a sign of victory over the oppressor of their generation, the modern-day Haman that destroyed about a third of the Jewish nation.

My father was born in Lodz, one of Poland’s main industrial cities and one of the largest textile centers in Europe. There were a quarter of a million Jews living in the city, and they comprised about a third of the total population. The city was full of shuls, chasidishe shtieblach and batei midrash. There was a large community of Gerrer chasidim in the city, and the Schwartz family was one of the most prominent. My grandfather Reb Avraham Yehudah, Hy”d, was the owner of a large steel factory, one of the largest in Poland. He was prominent and wealthy, the father of nine children. My father, Yaakov, was the youngest son. He studied in a Gerrer yeshivah that was located in a home of one of the chasidim of the city, but their hearts were always in the beis midrash in the town of Gora (Ger in Yiddish), which was not far from Warsaw. The father and son were devoted to the Imrei Emes of Ger, zt”l, and from time to time they went to visit him and gain strength from being in his presence.

While in the yeshivah, young Yaakov became known for his artistic talent. He had the ability to write beautiful calligraphy in Stam, though he never had any professional lessons. One of his closest friends in the yeshivah was his chavrusa Aryeh Yehuda Leib Kutner who later became one of the most prominent Gerrer rabbanim in Tel Aviv.

In 1939, when my father was 22 years old, World War II broke out. Lodz was stormed by the German army. The Nazis changed the city’s name to Litzmannstadt and turned it into an industrial center to serve the German army, the Wehrmacht. Soon after, the Germans decreed that all the Jews of the city had to relocate to the poor part of Lodz. They surrounded this squalid area with a wall and turned it into a ghetto. They built factories in the ghetto and forced the Jews to work there, amid hunger and disease. The head of the ghetto’s Judenrat (Jewish council) was Chaim Mordecai Rumkowski. He was given complete authority by the Nazis to “take all necessary measures” to maintain order in the ghetto, earning the nickname King of the Jews. Rumkowski forced the Jews to work hard to satisfactorily meet the German quotas. Tragically, the Germans started to send the elderly Jews to the death camps, and my father’s grandparents were taken away. Then they sent the little children for extermination. Those who remained in the ghetto worked as hard as they could, though they suffered from starvation.

Close to a quarter of a million people were virtually imprisoned in a very small area.

Acquiring food became the most vital activity. I remember my father telling me: “We were in a small room, along with my brother and five sisters. My mother and grandmother had died of starvation. It was so bad that I would collect leaves from the road as I walked back from the factory, and I would boil them in water, so my family would have something resembling soup to eat. Most of the Jews did not survive the war, only the strong and young.”