What defines a life?

The greatest misfortune to befall my mother, in her eyes, was having been born to a practical woman. Until the day she died, throughout a life that spanned three continents, she believed that wishing for something with all your heart made it come true, that a little magic never hurt anyone, and if you thought about something really hard, someone else would surely hear it. She also believed that the power of beauty could overcome anything.

But then again, my mother wasn’t the perpetrator of evil, only its witness.

My grandmother grew up in Bialystok, Poland, at a time when everyone knew everyone, life centered around the shtiebel, and for the most part, the rhythm of days had a distinct certainty. When all of that came crashing down and wickedness didn’t lurk in cracks and seep under windows but roared in, a fury unchecked, carrying swastikas, death and the demise of our people, few survived, and no one remained standing or whole.

Against the dwindling colors of a world gassed to death, my mother, lover of splendor, art, literature and her daughters, never stood a chance.

But she tried. Oh, how she tried.

Whether my grandmother had two sisters or four is just one of the many facts that was erased by the almost-successful expunging of the Jews. There is simply no one alive left to ask. But in the late 1930s, it was time for Chana to marry. For her first date with Chaim, my grandfather-to-be, she borrowed a classic dress from one sister and smart shoes from another. The dress fit. The shoes did not.

A shy, soft-spoken, sweet man, Chaim hoped for a woman who would love him and be without any obvious abnormalities. Only one of his wishes would come true. Chana later proved to be too bitter, too broken, her heart shattered in too many places to truly love a husband. And on that first date, hobbling around on feet covered in blisters, Chaim wondered what was wrong with this girl.

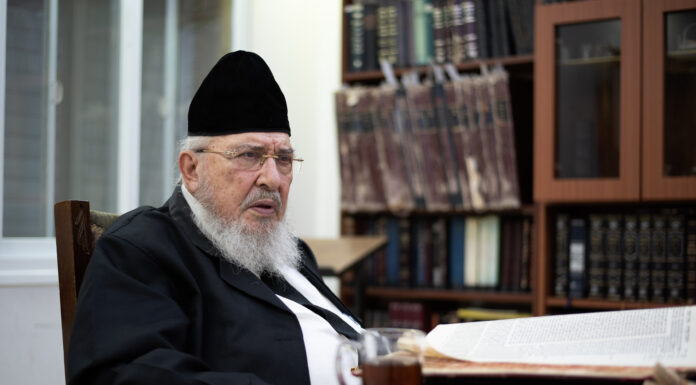

They were married to the tune of a ghetto existence and a way of life ending forever, not by choice but simply because there was no one to prevent the ruin. And the insistence of their grandfather, who also happened to be a rabbi, that my grandparents, Chaim and Chana, young, strong and still childless in the early phase of marriage, should leave Poland and go to Belgium to find work and send back money. No amount of tears or tantrums from the young bride who had never even stepped past her village could change this decree. But to ease the ache, they were promised that they could come home a year later. Certainly, this madness couldn’t last another year.

They didn’t grasp that the world would keep on turning while we went up in smoke.

They didn’t understand that by the time my grandparents could return, their granddaughters would already be bickering as kids do, their daughter sentenced to being crushed by the birthright “you survived,” and nothing in this universe would make my grandparents want to step foot in Poland.

Two girls born within a few months of each other. One in Poland. One in Belgium. First cousins. One would perish in Auschwitz. The other would spend the rest of her life answering to the cries of her spirit.

“You survived,” always going thump-thump-thump in the crevices of her mind. I want the pretty sweater, Maman. You survived. I want to be with my friends. You survived. I want to go dancing. You survived. I want… But. You. Survived. There was no space left in the solid, not-to-be-cracked wall of their being. No air remained between the effort of the in and out it took just to breathe to allow for the little niceties occasionally offered by life: here is a gift, enjoy it, take it while it’s available, before it expires, before the hardships continue to mount. You survived. Because when the backdrop of your world is black soaked with red, what happens to the girl who cherishes pink? But that would come later.