IT ALL STARTED IN BERLIN

The process that would lead to the appointment of an American ambassador to counter anti-Semitism began, appropriately enough, in Berlin in 2004. In response to a wave of anti-Semitic incidents in Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe—a regional security group to which 57 countries belong—organized a conference in the German capital to discuss ways to combat the problem.

US Congressman Tom Lantos of California, who was the only Holocaust survivor in Congress, took a particular interest in the conference. He pressed Secretary of State Colin Powell to head the US delegation to the Berlin event, believing that Powell’s presence would attract the high-level diplomatic and media attention that the problem of anti-Semitism needed.

Secretary Powell reluctantly agreed—and then proceeded to deliver groundbreaking remarks that no one expected. “It is not anti-Semitic to criticize the policies of the State of Israel, but the line is crossed when Israel or its leaders are demonized or vilified; for example, by the use of Nazi symbols and racist caricatures,” Powell declared. That was the first time a senior US government official recognized that comparing Israel to the Nazis crosses the line between legitimate criticism and outright bigotry.

Inspired by Powell’s speech, Congressman Lantos conceived the idea that the US government should take on the task of leading an international fight against anti-Semitism. Lantos introduced a bill called the Global Anti-Semitism Review Act, to create a position of US envoy for monitoring and combating anti-Semitism around the world.

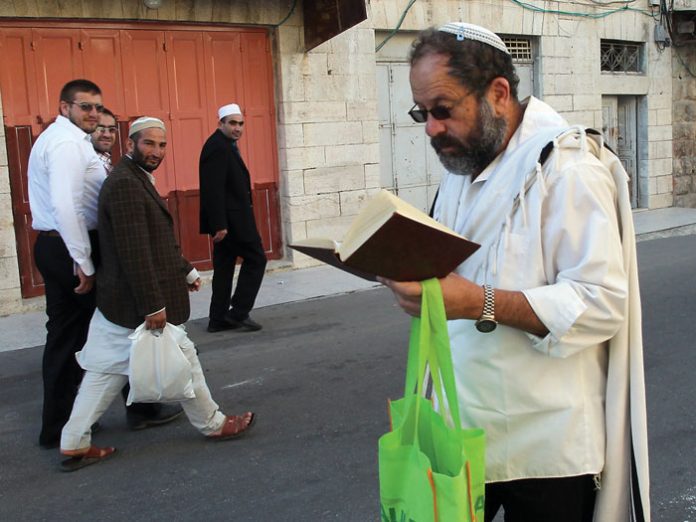

Lantos and his supporters argued that the US has a strategic interest in fighting anti-Semitism, because hatred of Jews is now intertwined with hatred of America in the ideology of Muslim terrorist groups. They also cited America’s history of speaking out against human rights abuses around the world as a precedent for action against anti-Semitism globally.

“NO PREFERENCEFOR JEWS”

To Lantos’ surprise, the Bush administration opposed his bill. In July 2004, the State Department issued a memorandum arguing that the US government should not give “preference” to any “single religious or ethnic group,” and any focus on anti-Semitism would be showing “favoritism” to Jews.

State Department officials said they supported a rival bill, introduced by US Senator George Voinovich (R-Ohio) and Rep. Chris Smith (R-New Jersey). That legislation would have required only a one-time report by the State Department on anti-Semitism, and it would not have created any ongoing position of envoy, as Congressman Lantos was proposing.

Lantos was dismayed by State’s “favoritism” argument. Jews were being singled out for attack in Europe, and the Free World needed to respond. “I’m unaware of an outbreak of anti-Episcopalian feeling throughout Europe,” he declared.

The congressman also detected an element of hypocrisy in the State Department’s stance. While State was claiming that an office focusing on anti-Semitism would be giving unfair preference to a particular group, the department “currently has statutorily mandated offices on Tibet, Women, Human Trafficking, and Religious Freedom,” he argued.

Anti-Israel groups weighed in, too. The militant Council on American-Islamic Relations rejected the Lantos bill on the grounds that “hate incidents aren’t…exclusive to one group of individuals.” A leading pro-Arab magazine, the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, called the Lantos legislation “outrageous.”

LEARNING FROM HISTORY

That’s when my colleagues and I at the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies decided to get involved. Our work focuses on America’s response to the Holocaust, so we were particularly troubled by the State Department’s position against “singling out” Jews for special attention. That reminded us of the position the State Department took in the 1940s, when it tried to downplay the Jewish identity of Hitler’s victims.

Perhaps the most infamous expression of that attitude took place when then-Secretary of State Cordell Hull met with the British and Soviet foreign ministers in Moscow, in October 1943. Afterwards, they issued a statement condemning the Nazis for their war crimes against “French, Dutch, Belgian or Norwegian hostages,” “Cretan peasants,” and “the people of Poland”—but no mention of the Jews.

The following year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not even mention Jews in a White House message commemorating the first anniversary of the Jewish revolt against the Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Sixty years had passed, yet the State Department still seemed to regard the Jews as a people whose suffering merits no special attention, even when they are being singled out by their persecutors.

To counter the State Department’s opposition, we prepared a petition arguing that “it is the anti-Semites who are singling out Jews, and that is why the fight against anti-Semitism deserves specific, focused attention.” It attracted a wide-cross section of Americans of all religious and political stripes.

The signatories included prominent Republicans such as Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick and former vice-presidential candidate Jack Kemp; former CIA director R. James Woolsey; former National Security Adviser Anthony Lake; President Clinton’s envoy for Holocaust issues, Stuart Eizenstat, and even several former State Department officials.

Many Christian leaders also signed, including the presidents of the Union Theological Seminary and Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary, and deans of the Yale University Divinity School and the Drew University Theological School, as well as First Things editor Father Richard John Neuhaus.

The petition received wide publicity, and in the days to follow, the tide began to turn. Congressman Smith suddenly announced that he was withdrawing his bill and endorsing Lantos’ legislation instead. Senator Voinovich followed suit. The State Department then backed down, and in early October, both the Senate and the House passed the Lantos bill.

Despite having previously opposed the legislation, President Bush decided to use it as ammunition in that year’s closely-fought presidential race. On the eve of campaign appearances in heavily-Jewish West Palm Beach, the president signed the Lantos bill into law. The Miami Herald reported that “at every stop” in Florida, “Bush told the crowd that he’d earlier in the day signed” the Lantos bill to fight anti-Semitism. Four years earlier, Bush had been elected after winning Florida by a mere 537 votes. He knew that every Jewish vote in Florida carried weight.

A DOUBLE STANDARD

The Lantos bill did not specify a date by which the new Envoy for Monitoring and Combating Anti-Semitism had to be named. But it did require the State Department to issue an annual report on anti-Semitism around the world, and the first report appeared in early 2005, before the ambassador had been selected. It was clear from the slant of the report that the ambassador was going to have his work cut out for him.

The report gave only passing attention to anti-Semitism sponsored by Arab regimes with which the Bush administration had friendly relations. But when it came to countries where anti-Semitism is not promoted by the government, the State Department had plenty to say.

The section on Saudi Arabia was only 182 words long; Iceland was given more than twice as much space. The Palestinian Authority’s section was 86 words; Armenia (194), Brazil (149), and Azerbaijan (142) were allotted much more space. It seemed the State Department was trying to avoid offending some of the worst offenders in order to avoid ruffling diplomatic feathers.

Eighteen months after the Lantos legislation was signed into law, President Bush finally chose the first ambassador for fighting anti-Semitism: Dr. Gregg Rickman, a former aide to US Senator Alfonse D’Amato (R-New York), who had worked extensively on Holocaust restitution issues. His job was to keep track of anti-Semitic incidents around the world (although not in the United States), contact officials of countries where anti-Semitic outbreaks took place, and draw public attention to the problem.

Ambassador Rickman issued his first report in late 2007. Once again, the anti-Semitism of Arab regimes received sparse attention. The report did not mention the Palestinian Authority’s publication of anti-Semitic statements in its media or schools. It noted that in Saudi Arabia, “there was substantial societal prejudice based on ethnic or national origin,” but it did not mention that the prejudice is promoted in government-controlled media, schools and mosques. Rickman’s report complained about an anti-Jewish series on a private Egyptian television station, but it didn’t say anything about the anti-Semitic programs on government-controlled television stations.

Washington sources attributed the slant to pressure on Rickman from senior administration officials. His hands were being tied because of the administration’s goal of not irritating those regimes.

The State Department subsequently changed the reporting procedure. Instead of having the anti-Semitism envoy issue his own annual report, the envoy merely “provides input on anti-Semitism” in the drafting of two other Congressionally-mandated annual reports from the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor—one on human rights practices around the world, and the other on international religious freedom.

This has had the effect of taking some heat off the anti-Semitism envoy, since it is impossible for the public to know which parts of the Bureau’s reports the envoy composed or had “input” in.

NEW CONTROVERSIES

Because the position of Envoy for Combatting Anti-Semitism is a political appointment, the ambassador is replaced with each new administration. Gregg Rickman left the post in January 2009, following the inauguration of Barack Obama as president. It took the Obama administration eleven months to choose his replacement: Hannah Rosenthal, a women’s rights activist and former head of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs.

Rosenthal also had been active in J Street, the left-wing lobbying group, leading the Orthodox Union to express concern that her political views might affect her performance in the new position. Soon after taking up the post, she stirred controversy by publicly criticizing the Israeli ambassador to the United States, Dr. Michael Oren, for not attending a J Street conference.

“I stand by the statement I made about Michael Oren,” Ms. Rosenthal said this week in an exclusive interview with Ami. “Increasingly, mainstream Jews are disconnecting from Israel advocacy, and I think it is important that Israel’s emissaries understand why that is happening.” She added that she and Oren later became friends, “and I have nothing but positive things to say about him.”

In a number of speeches delivered abroad in 2009-2010, Ambassador Rosenthal addressed the issue of prejudice against Muslims. That prompted strong criticism from her predecessor, Gregg Rickman. “Is she the Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Anti-Semitism or Islamophobia?” Rickman wrote. “It seems that our country’s point person on anti-Semitism is highly confused and has spent the past seven or so months fighting the wrong fight.”

Rosenthal told Ami that she regarded her outreach to Muslims as an important part of her work. “I was always looking for a way to get ‘other people’—non-Jews—to condemn anti-Semitism,” she said. “As the child of a Holocaust survivor, it is not headline news that I would condemn Holocaust denial. But having a group of imams condemn it was more powerful and impactful.” She believes she was successful in “building coalitions with Christians, Muslims and other faith communities,” and “in no way did my work on building alliances take away from calling out anti-Semitism.”

Looking back on her service as envoy for combating anti-Semitism, Rosenthal told Ami that her most important accomplishment was “instituting training for our foreign service officers on what anti-Semitism is. I counted on our field offices to let me know if things were happening, but if they did not know what anti-Semitism is, they couldn’t let me know.”

At the same time, she acknowledged some of the limitations involved in the work. “Sometimes I felt that some people in various [US government] offices had ‘clientitis,’” she told Ami. “Meaning that they were so close to their contacts in a country, they didn’t want to rock the boat. This rarely happened, but it did occur and it was very frustrating.”

WAITING FOR THE

NEW AMBASSADOR

In July 2012, Rosenthal announced she would be leaving her position in order to become president of the Milwaukee Jewish Federation. Once again, there was a long delay in selecting her replacement. It was not until May 2013 that the Obama administration replaced her with Ira Forman, the Jewish outreach director for the Obama presidential campaign.

Following the inauguration of Donald Trump as president in January 2017, Ambassador Forman resigned. No successor has yet been named in the 16 months since then. The delay is comparable to that which preceded the choices of Rickman (18 months), Rosenthal (11) and Forman (9), and it appears to result from the same cause: fierce behind-the-scenes jockeying among several factions within the administration, each of which has its own preferred candidate.

There is also a faction within the State Department that would like to see the position abolished altogether. Senior State Department officials were openly unhappy with the creation of the post in the first place, and some are said to still regard the envoy as a nuisance.

In February 2017, Bloomberg News reported that the White House was considering eliminating a number of special envoy positions, including the envoy for combatting anti-Semitism, as a budget-cutting measure.

In June, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told a House of Representatives committee hearing that the Trump administration might fold the anti-Semitism monitoring office into another division of the department. “One of the things that we are considering—and we understand why [special envoys] were created and the good intentions behind why they were created—but one of the things we want to understand is by doing that, did we weaken our attention to those issues? Because the expertise in a lot of these areas lies within the bureaus, and now we’ve stripped it out of the bureaus,” Tillerson testified.

The indications that the anti-Semitism envoy might be eliminated prompted widespread criticism from Jewish organizations and members of Congress, as well as a letter of protest signed by more than 100 Holocaust scholars and organizations. As a result, the administration backed down and said it will “soon” fill the vacant position.

CHOOSING A FIGHTER

The idea of the US government leading the fight against global anti-Semitism understandably has strong appeal to the Jewish community. Moreover, elimination of the envoy’s position could be seen as lending weight to recent accusations by liberal Jewish groups that the Trump administration is insufficiently concerned about the problem of anti-Semitism.

At the same time, critics ask what value the envoy’s work will have, if his or her hands are tied by political considerations. If, as Hannah Rosenthal said, some US officials are “so close to their contacts in a country, they didn’t want to rock the boat,” it can result in pressure on the envoy to refrain from focusing on anti-Semitism that is promoted by regimes that are favored by the White House or State Department.

The Congressionally-mandated US fight against global anti-Semitism stands at a crossroads. If the next envoy is compelled to adhere to political limitations, it could be worse than having no envoy at all. The credibility of the US effort to combat anti-Semitism will depend on choosing an envoy who is not only ready to lead the fight, but is allowed to fight without one hand tied behind his back. l