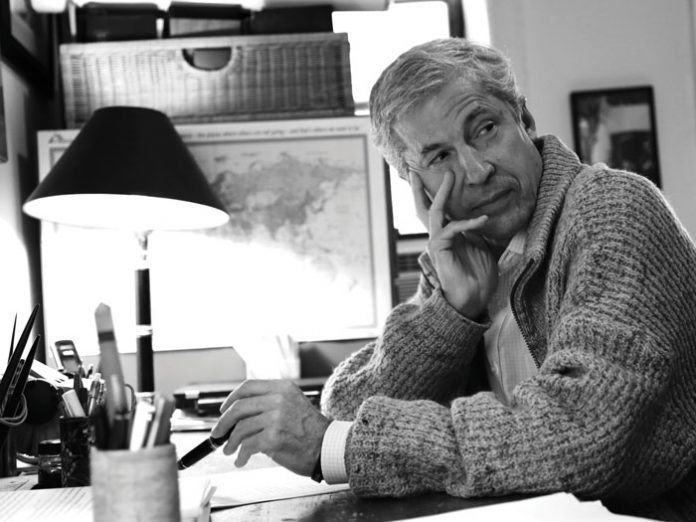

That is how veteran journalist Jere Van Dyk describes his capture, in Afghanistan in 2008, by the Taliban, in his recent book, The Trade: My Journey into the Labyrinth of Political Kidnapping.

He would be held for 45 days.

Van Dyk faced death the entire time he had been in captivity. He was subjected to two mock executions; Van Dyk had covered the 2002 abduction and murder of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in Pakistan and knew very well what could have happened during his own abduction. And yet his emotional connection to the region he’d been involved in for over 35 years was so strong that even when he was eventually released by his captors and brought to a US military base where FBI agents escorted him into a building for food and a shower, at first he refused it all.

As he writes: “I didn’t say it but I didn’t want to leave the mountains.”

In his mental state at that moment, washing off the scent of the mountains would mean leaving.

When I recently spoke with Mr. Van Dyk, I asked him why he would feel that way.

“Because there was this love I have of the people from before, even today, who’ve always been so good to me,” he told me. “And because there’s this element of living on the edge that I knew I would never be able to replicate. I had this romantic idea in my mind from the ’80s, which is what led me to trouble. There’s this romancing of the past. So many years I held onto the past. I realized it was over, but I didn’t want to leave; I didn’t want to go back and be normal.”

But one suspects that there may have been more to that impulse. He also told me that, in some ways, once you’re a captive, nothing is ever the same.

Some of the things that linger most for him are the questions he wanted answered about his captivity: Why had he been captured, and why, unlike Daniel Pearl, had he been released?

Those questions were part of the reason that in 2014, six years after his release, Van Dyk took the surprising step of returning to Afghanistan, to try to answer those questions. In his new book, he shows just how many questions remain for hostages after they are released, and how hard it is to answer any of them.

The expert

“The first time I saw Afghanistan was in 1973,” Van Dyk writes. “I was going to buy a car and drive across Asia, and I’d asked my parents—devout Plymouth Brethren in Washington State—if Kody, my younger brother could join me.” The two brothers drove all the way from Germany to Kabul. The two of them traveled around Afghanistan and Pakistan, having adventures and misadventures (Kody ended up in jail for a short time when his visa ran out), and then headed home.

That trip, a relaxed vacation of two brothers in what was then a relatively liberal country, started Van Dyk’s fascination with the region. In 1974, he became an aide to Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, but when the USSR invaded Afghanistan in 1979, he got himself a contract from The New York Times to report on the war.

Van Dyk flew to Pakistan and met with mujahideen leaders, as well, including Yunus Khalis, who would become Osama bin Laden’s mentor.

“He was different,” Van Dyk writes. “I sat on the wood floor with him. He had a long gray beard and wore a bandoleer. He carried a pistol. He had a deep voice and looked to be in his seventies.” Sitting with Yunus Khalis was a young man, Din Mohammad, who would eventually become an important Afghan tribal leader and politician, as well as a good friend of Van Dyk’s and a central figure in the intrigue surrounding his kidnapping by the Taliban.

With Yunus Khalis’ approval, Van Dyk managed to embed himself with a group of mujahideen, led by Jalaluddin Haqqani. Haqqani would eventually head what is known as the Haqqani Network, a Taliban- and al-Qaeda-affiliated group (Osama bin Laden began his jihadist career as a member of the Haqqani Network) that has been one of the most dangerous militant groups in Pakistan and Afghanistan, designated terrorists by the US and Pakistan.

But back in 1979, they were being supported by the US, to fight the Soviets. Van Dyk joined them in sneaking across the border into Afghanistan, where he saw the Soviet war machine and the devastation it had wrought on the villages there.